- Consumer 150

- Posts

- Durables on a Diet: Why Big-Ticket Spending Isn’t What It Used to Be

Durables on a Diet: Why Big-Ticket Spending Isn’t What It Used to Be

Consumer spending on durable goods in the U.S. is entering a new, quieter phase.

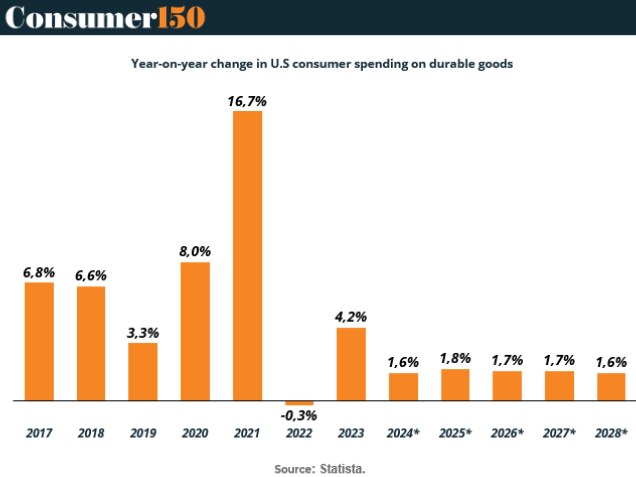

After a pandemic-fueled spike of +16.7% growth in 2021, durable goods spending is projected to level out, stabilizing at an annual growth rate of just ~1.6%–1.8% through 2028, according to Statista. But beneath this seemingly flat surface lies a story of inflation, substitution, and shifting value equations that’s reshaping consumer behavior—and investor strategy.

The durable goods rollercoaster began with COVID-19. As services collapsed and households stayed home, consumers redirected spending into cars, furniture, electronics, and fitness gear. That demand shock—turbocharged by stimulus checks, led to the category’s historic 2021 jump. But as the chart shows, the momentum didn’t last: by 2022, durable goods spending declined (-0.3%), and now sits on a low-growth plateau.

So, are Americans done buying big stuff? Not exactly.

In real terms (adjusted for inflation), durable goods purchases have actually more than tripled since 2000, far outpacing the 58% rise in services. What’s changed is the price trajectory: durable goods have gotten cheaper, while services have gotten more expensive. Since 2000, the average price of durable goods is down 25%, with some categories—like video and information equipment, seeing price drops of up to 86%. Services, meanwhile, have climbed nearly +97%, thanks largely to wage-linked inflation.

This explains why nominal spending (actual dollars out the door) on services has risen faster, even as people bring home more physical stuff. Think of smartphones: they're far better and cheaper than 20 years ago, but they now serve as multifunctional devices replacing several separate products.

Inside the durable goods basket, recreational goods and vehicles, including home entertainment systems, laptops, and fitness equipment, have seen the biggest gains in volume. Meanwhile, motor vehicles and parts, once the dominant category, are slipping in share as prices rise and replacement cycles stretch. This compositional shift suggests consumers are investing in smaller, multifunctional items rather than traditional big-ticket purchases.

Zooming out, the trend reflects broader economic dynamics. With inflation cooling, real personal consumption expenditures (PCE) are expected to grow at a steady pace. Durable goods will still matter, but they’ll no longer lead the charge like they did post-2020. Services will regain dominance, fueled by pent-up demand, higher wages, and rising labor costs in health care, education, and travel.

Investors and brands should adjust accordingly. Durable goods are becoming more commoditized, which means tighter margins and greater emphasis on features, durability, and digital integration. Think: smart appliances, modular upgrades, or hybrid service-subscription models.

At the same time, consumer wallets are under more pressure. With credit card debt surpassing $1.1 trillion, and personal savings rates dropping to 3.4%, households are getting choosier about where and how they spend. And while the Fed’s future rate cuts may lower borrowing costs, a softening labor market could dampen confidence.

Bottom line: The durable goods boom was real, but fleeting. What comes next is a phase of optimization, not accumulation. For consumers and companies alike, it’s not about buying more, it’s about buying better.